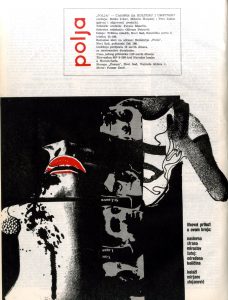

Polja was founded in 1955. At the time, the magazine’s editorial staff and correspondents were young and unknown writers, critics, and artists, which distinguished Polja from other similar Yugoslav magazines. Since its establishment, the magazine has explored culture, art, and social issues.

Polja’s launch was closely connected with

Tribina mladih [Tribune of Youth], an organization of students from the University of Novi Sad.

Tribina mladih recruited members, mostly artists, who were critical towards both contemporary art and the state.

Polja published literary, film, and art criticism, alongside with as well as translations of artistic and theoretical texts from both abroad and from minorities living within Yugoslavia. Prints of contemporary visual art were also included with the articles.

Polja employed dozens of publishers and permanent correspondents, including eleven editors in chief, each with a different approach to both art and politics. Publishers included the state-run publishing house PROGRES, and

Tribina mladih, which indicates that the project was state funded. Because of this, it is difficult identifya unique political position of Polja within Yugoslavia. Nevertheless, the magazine was an important platform for promoting unknown artists, though some proved to be more critical towards society than others. In the late 1970s,

Polja’s circulation reached 5,000 copies. Compared to

Letopis Matice srpske, literature journal in Novi Sad with a circulation of 800 copies,

Polja reached a significantly greater number of readers.

In communist Yugoslavia, youth publications were seen as a direct reflection of youth political opinion. Thus, the state deemed these projects important, and provided funds to finance them. Because of this, projects were strictly controlled. One example of this control is the case of Student, the University of Belgrade’s student-run magazine. During its publication, several issues of Student were banned, and the editorial boards were replaced. Polja, on the other hand, accepted influence from the authorities in its attitudes toward local neo-avantgarde artistic groups.

In late 1960s and early 1970s Novi Sad was an important center for postwar avant-garde culture in Yugoslavia. Artistic groups such as KÔD [CODE] formally formed artistic group in 1970 as well asJanuar [January] and Februar [February], where informal artistic groups presented provocative performances that shaped the neo-avantgarde in Novi Sad. The artists active in these groups were part of Tribina mladih and contributed to magazines that included Polja and Új Symposion. One exhibition at Tribina mladih,in January 1971, provoked particularly fierce critique; works presented included a bank note surrounded by swear words. Tribina mladih was also accused of showing forbidden films, known as movies "from the bunker.” Pressure on artists ultimately led to aconflict between Novi Sad's alternative art and moderate modernist communities. The intersection between these two artistic viewpoints ultimately developed into a cultural perspective adopted by Tribina mladih, Polja and Új Symposion. Belgrade-based weekly NIN and the newspaper Večernje novosti began to report on the situation. The dissolution was dramatic; representatives of Tribina mladih were replaced, and two active contributors to Tribina, Miroslav Mandić and Slavko Bogdanović, went to prison for articles published in Új Symposion and Student. Polja's editorial board also underwent changes as itbecame more strictly controlled.

In addition to the pressures that controlled writers’ choices of topics and the expressions of freedom, Polja also experienced government pressure from the Autonomous Province of Vojvodina. As they were published in Novi Sad, the capital of the autonomous province, authorities attempted to make Polja a provincial newspaper, expected to argue against the Belgrade press, with a strong political leaning towards Vojvodina’s political leadership. When they refused, Polja was attacked for being a publication that supported liberal Belgrade circles and promoted Western ideas.

Jovan Zivlak, editor-in-chief of Polja from 1976 to 1984, explained in an interview with COURAGE that his editorial board sought to avoid trouble, but that the Communist Youth Union stressed“ a concept of culture that has constantly encountered resistance. We constantly endured the pressure of publishing councils that ordered us to either change our concept, or be shut down.”This pressure primarily affected the authors’ choices of topics, but Zivlak pointed out the influence that prevailing bureaucratic language had on the result “a completely prescribed jargon about socialist values, socialist culture, and the construction of a socialist person ,” which he found unacceptablebut was insisted upon by authorities.

Though Polja managed to reach a distribution of 5,000 copies, they were often condemned by the Novi Sad pubic. “Polja were taken as not local enough and that they do not address the population that creates here. Although we did not ignore that (the local literature, aut.),” Zivlak explains. The communist authorities of Vojvodina observed how Polja reached a wider Yugoslav audience and raised topics that were not allowed. Jovan Zivlak compares Voyvodina's regime with Stalinist methods: “Only, there was no prison. But the ideology, intimidation and methods of conversation were the same.” Government logic was to provoke conflicts between young and old: Novi Sad and Belgrade. The magazine was expected to identify with local views, and publications written by Belgrade authors provoked condemnations that included "cooperating with Belgrade circles," and “the duty-free import of Western ideas.”

Jovan Zivlak explains cultural opposition as “mastering and learning freedom” and the “belief in culture,” and stresses that political opposition was impossible.He says: “Do you mean: "There was a kind of deep consent among most intellectuals in this former country that culture, literature and philosophy are the foundation of our freedom. It was as if we shared something, some kind of secret. That was our cultural revolution, or cultural resistance.”

Until the disintegration of Yugoslavia in 1992, Polja was published using Latin characters. Afterwards, the magazine was published in Cyrillic. Publication was interrupted between 1992 and 1996, during the wars. Today, Polja is printed in Cyrillic by the Novi Sad Cultural Center. Today's editorial board believes that Polja has been instilled with a strong sense of closeness to the cultural space of Serbia and Montenegro, former Yugoslavia, Central Europe, and world literature.

In sixty-two years, 506 issues have been published. Of them,394 issues were published during the communist period (1955-1991). The Novi Sad Cultural Center has digitized all issues of Polja, which are now available to the public in the internet archive. The printed magazine can be found at theMatica Srpska Library in Novi Sad and at the National Library of Serbia in Belgrade.