Philosopher, painter. At the beginning of the 1920s, he participated in the illegal communist movement as a clerk. From 1928 to 1930, until his exclusion, he was a member of the Work Circle of Lajos Kassák. Following this, together with Pál Justus and Pál Partos, he became one of the leaders of the opposition in the illegal workers movement.

In the 1930s, he became a regular attendee of the lectures of the gnostic circle led by Ferenc Kepes (following in the footsteps of Jenő Henrik Schmitt). In 1931–32, he spent a few months in Germany on two separate occasions. He studied in Berlin at Karl Korsch and in Frankfurt at the lnstitut für Sozialforschung.

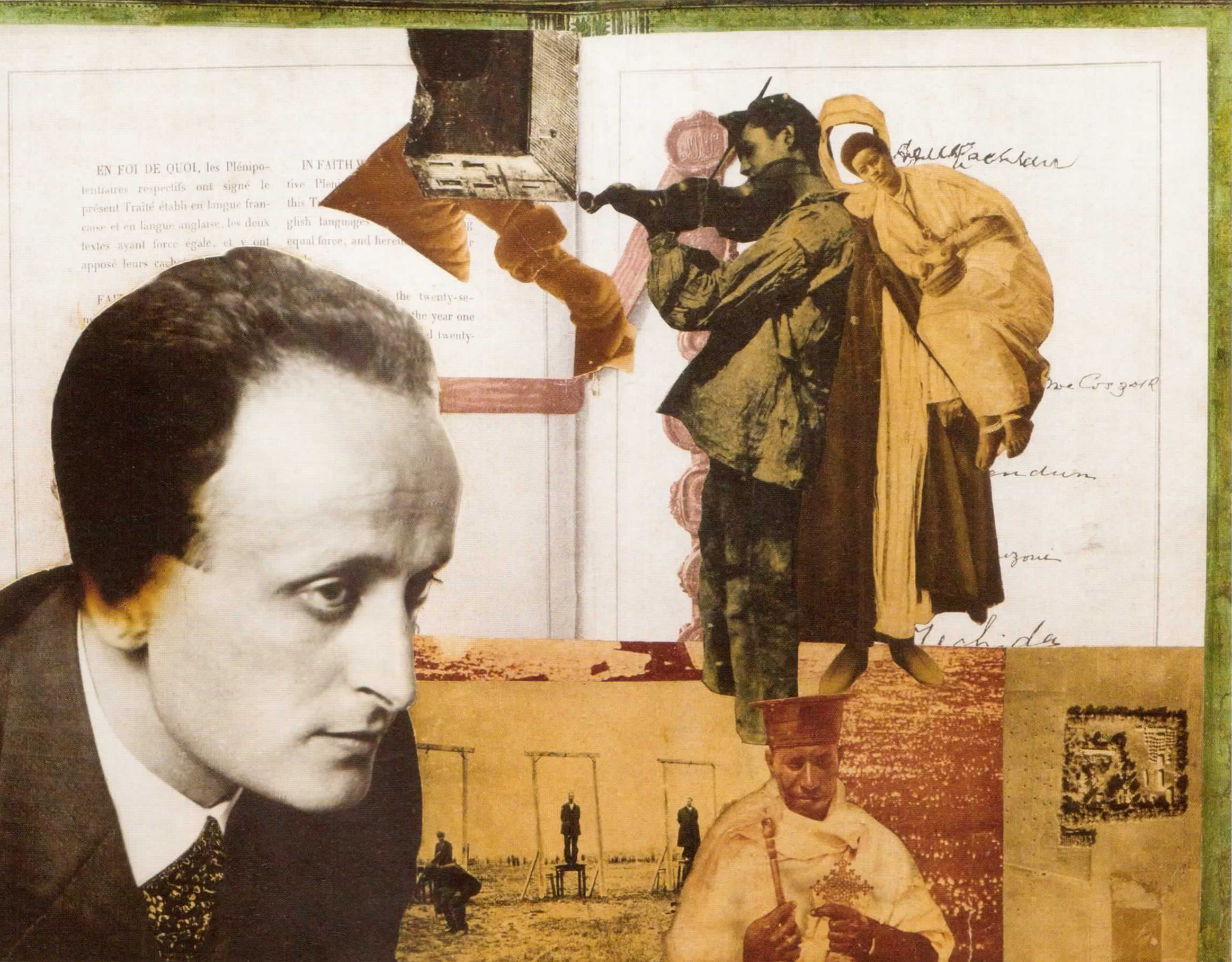

In 1933, he began to find the theoretical frames of Marxism narrow. Together with Béla Tábor and Zoltán Békefi, he became interested in the ideas of Freud and Jung, including their ideas about art. During a study trip to Vienna, the police accused him being a communist agent, so he went expelled to Paris. Here, he lived together with his friend Lajos Vajda for a year.

After his return, he offered a critique of sociology, Marxism, positivism, and psychoanalysis in a book written together with Béla Tábor (Vádirat a szellem ellen, [Indictment against the Spirit], 1936). The first part of the pamphlet A hit logikája [The Logic of Faith] was published in 1937 (the second part came out only after his death).

He wrote several essays in these years (Megjegyzések a marxizmus kritikájához [Some remarks on the criticism of Marxism], A tudományos szocializmus bírálatához [Some remarks on the criticism of scientific socialism], A mammonizmus természetrajzához [To the natural history of mammonism], Adalékok a halmazelmélet kérdéseihez [Contributions to the problems of set theory], Nietzsche, Biblia és romantika [Bible and romanticism]). They were published in print after his death.

He considered the anti-Semitic laws passed in Hungary a provocation, so he joined the synagogue in 1939. For a few months he served in the forced labor service, but he was demilitarized in 1940 due to pulmonary disease. In the spring of 1944, he was deported to Auschwitz. He was freed in January 1945.

In the autumn of 1945, together with Béla Hamvas and Béla Tábor, he launched the “Thursday conversations” series in the hope of radical spiritual revival. These gatherings were unofficial events held at the apartment of Tábor and his wife, Stefánia Mándy.

Between 1946 and 1948, he held seminars in private apartments for selected youngsters on subjects like the theory and psychology of values, the critique of set theory, language mathesis, and the theory of signs. In 1946, he wrote the essays “Művészet és vallás” [Art and religion] and “Irodalom és rémület” [Literature and horror]. In 1948 he withdrew from the group.

In 1954, he became a calligrapher himself. He considered his calligraphic works an addition to his philosophy. After the fall of the revolution, he emigrated with his wife and some of his followers in 1956 and lived in Brussels and Düsseldorf. He had exhibitions in several cities, including Brussels, Paris, Dusseldorf, and Essen. Many of his drawings he signed with the initials AO, his alias in the movement, which stands for Anti-Organization. This sign later became a visual symbol in his work.