Gheorghe Leahu was born on 10 May 1932 in Chişinău (also known as Kishinev, today in the Republic of Moldova) into a family belonging to the economic and political elite of Bessarabia, then part of the Kingdom of Romania. As a result of the Soviet ultimatum sent to the Romanian government on 26 June 1940, which called for the surrender of Bessarabia and Northern Bukovina under the threat of Soviet military invasion, the Romanian army and administration left the province. Before the Soviet troops entered Chişinău at the end of June 1940, Gheorghe Leahu and his parents moved to Bucharest. According to Leahu’s account, his grandparents, who remained in Chişinău, were arrested and executed by the Soviet troops as part of extensive repressive measures which targeted the elite of the province. In 1944, his father was wounded on the battlefield and transported to a hospital in Făgăraş, a small city in the south of Transylvania, near the mountains of the same name. Gheorghe Leahu, along with his mother and sister, moved from Bucharest to Făgăraş to take care of his wounded father. Subsequently, the Leahu family lived for several years in Făgăraş. After he graduated from high school in Făgăraş, Leahu attended the architecture courses of the Ion Mincu Architecture Institute in Bucharest between 1951 and 1957. There he had the opportunity to study under teachers who had had a Western education, and had been architects in interwar Romania, such as Duiliu Marcu, Octav Doicescu, and George Simotta. They instilled in him a respect for architectural heritage which would mark his entire activity.

After finishing his studies, he worked in the period from 1957 to 1991 as architect at the Bucharest Project Institute (Institutul Proiect Bucureşti), which was responsible for carrying out urban planning and architectural projects in the Romanian capital, and was in charge of designing the contemporary emblematic buildings of Bucharest in the 1970s and 1980s, such as the Unirea department store. In 1984, as an employee of the Bucharest Project Institute, he was charged with coordinating the architectural planning for the new building of the Bucharest Court of Law, which was to be situated, according to Ceauşescu’s instructions, on the site of the Văcăreşti Monastery, an important historic monument dating from the eighteenth century. Leahu and the team of architects he coordinated came up with twelve different architectural solutions which would have allowed the court of law to be built while at the same time preserving most of the site of the Văcăreşti Monastery. After two years of protracted debates, the authorities decided in 1986 to completely destroy the monument in order to make room for the new construction, rejecting all of the alternative proposals offered by Leahu’s team to save the monument. The very fact that Leahu received the task of coordinating the design of the new court of law in the Romanian capital suggests that he was accepted as a competent professional by the communist authorities, and that his initiatives to promote architectural heritage were tolerated, although not approved of.

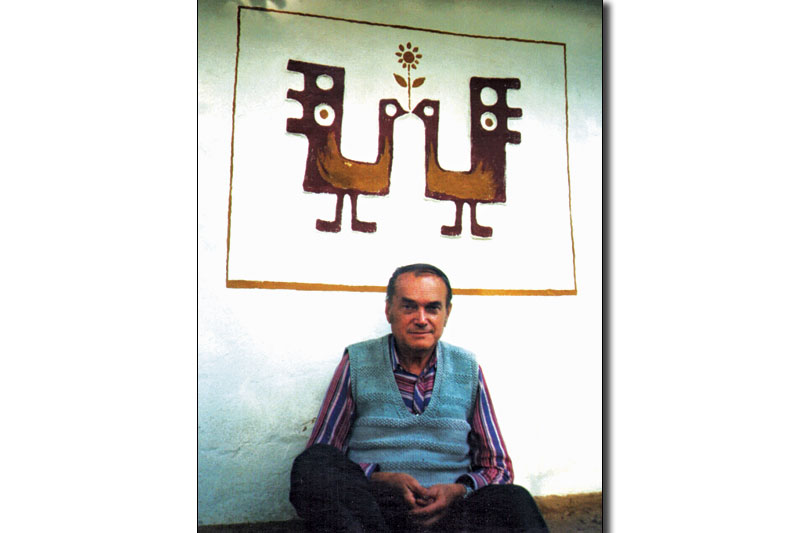

In the context of the limitations and stress of the professional environment, caused by the interference of those in political power, one of Leahu’s means of escape was to paint watercolours. He started painting watercolours when he was in high school. In the 1980s, given the frustration caused by the degradation of working conditions for architects, who turned themselves into mere witnesses to the demolition of numerous historical monuments without attempting to protest, Leahu started his own silent act of cultural opposition by painting watercolours as a way of escaping the gloomy atmosphere of everyday life. He painted mostly old streets and buildings in Bucharest and other Romanian cities. His watercolours represent a source of information for large areas of the Romanian capital, which were destroyed in the 1980s in the restructuring of Bucharest, a process legitimised by the official discourse concerning the “urban systematisation” of the capital, which presented the demolitions as a necessary step in modernising the city. The watercolours represent an alternative memory to the official discourse of the time, which attempted to limit the protection and promotion of the city’s architectural heritage, and especially of the city’s old churches. A series of watercolours representing urban landscapes in the old centre of Bucharest were gathered by Leahu in an album entitled Bucureşti – arhitectură şi culoare (Bucharest – architecture and colour) and sent for publication in 1986 to the Sport Turism Publishing House. Initially, the album was approved by the censors and was published in 1988, probably due to a lapse of censorship activity, but, because it contained reproductions of watercolours representing old churches, it was withdrawn from sale and all but a few copies were destroyed.

Leahu kept a secret diary between 1985 and 1989, which he hid in his garage. The years discussed in the diary were characterised by a drastic rationing of basic products, as well as by a more repressive political regime, an intensification of censorship and propaganda, especially in the form of Ceauşescu’s personality cult. In his diary, Leahu harshly criticised Ceauşescu’s regime and its policies, which turned everyday life into a desperate struggle for food or other consumer goods, and professional activity into a long line of humiliations.

After 1989, Leahu exhibited his watercolours in Romania and abroad (New York – 1992, Vienna – 1994, Chicago – 1995, Paris – 2001, Venice – 2002). He also published a series of albums containing selections of reproductions of his watercolours, such as: Bucureştiul dispărut (Lost Bucharest, 1995), Distrugerea Mănăstirii Văcăreşti (The Destruction of the Văcăreşti Monastery, 1997), Bucureşti – portretul unui oraş (Bucharest – Portrait of a City, 1999). In 2005, he published his secret diary from the 1980s, under the title: Arhitect în „Epoca de Aur” (Architect in the “Golden Age”). The Romanian Post Office issued a series of stamps reproducing Leahu’s watercolours, which illustrates the manner in which his work marked the visual culture of post-communist Romania. As a sign of appreciation for his entire activity, Leahu was included in various professional organisations, such as the National Commission for Historic Monuments and the leading structures of the Union of Architects of Romania. In 2004, he was decorated by the President of Romania with the Order of Cultural Merit, rank of Commander, for his contribution to promoting Romanian culture.