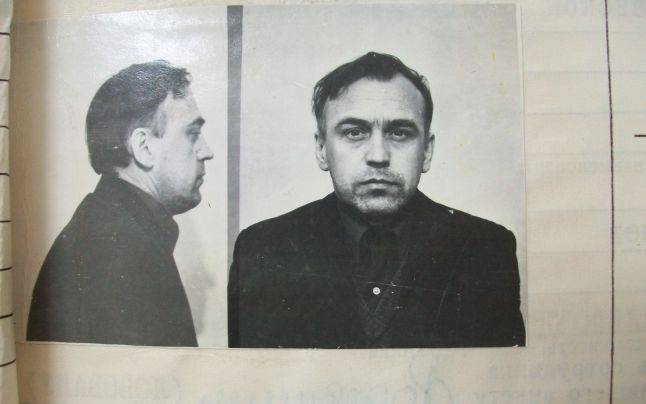

Viktor Koval (born in March 1941, Komsomolsk-on-Amur, Khabarovsk Region, RSFSR) was an engineer who came to the Moldavian SSR (the city of Bălți) in 1974, after previously working in various cities of the Russian Far East and the southern region of European Russia (such as Novorossiisk). Koval was of Russian ethnic background and came to the MSSR along with many other engineers and technicians of Russian extraction who staffed the expanding industrial enterprises of Soviet Moldavia during the 1960s and 1970s. At the time of his arrest in March 1982, Koval had been working for the past five years as a head engineer at an electrical equipment plant, in the section dealing with construction works. According to the material of the official investigation, Koval began to openly express ”anti-Soviet” opinions in late 1977, mainly at his workplace. He was very critical of the Soviet political structure, in general, and the electoral system, in particular, claiming that Soviet citizens lacked any real civil liberties and political rights, while deputies were pre-selected by the party instead of being elected by the people. The KGB correctly identified the Western radio stations which Koval used to listen to (Voice of America, Radio Free Europe/ Radio Liberty, BBC, etc.) as the major sources of his criticism and discontent. This coincided with the regime’s own fears of foreign propaganda, but also proved the real impact of the “enemy stations,” despite Soviet jamming efforts.

The most serious incident linked to Koval’s rejection of “Soviet democracy” occurred on 4 March 1979, when he adamantly refused to take part in the token elections for the Supreme Soviet and argued his position in front of the members of the electoral commission. The case files point to a growing radicalisation of Koval’s views during the next two years. Thus, in early 1980 he criticised the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, claiming that it was in fact a case of brutal interference in the internal affairs of a sovereign state rather than an example of “internationalist assistance,” as the official propaganda insisted. Even more serious from the authorities’ perspective was Koval’s open support for Polish Solidarity. In August 1980, he praised the Gdansk workers’ revolt as a model of true democracy and “people’s power,” contrasting it with the sham democratic credentials of the Soviet regime and the purely formal existence of Soviet trade unions. In late 1981, he condemned the brutal police repression of the Solidarity movement and the declaration of the state of siege, viewing these events as a suppression of the people’s will. These opinions led the KGB officials to conclude that they were dealing with a particularly dangerous case of anti-regime attitudes. This was also confirmed by the search of Koval’s apartment, which led to the discovery of a number of papers and notes with an “anti-Soviet” content. He did not spread or propagate his views in written form (aside from the small incident with the leaflets found near his factory in early 1982), but was quite frank in his conversations with his co-workers.

Following the trend of using punitive psychiatry in order to suppress open opposition, Koval was subject to a psychiatric evaluation, which found that he suffered from “latent schizophrenia,” despite the fact that the evidence was not convincing. Rather than receiving a prison sentence, on 27 August 1982 he was sent to a special psychiatric facility of the Soviet Ministry of Internal Affairs located in Dnepropetrovsk (Ukraine). During the Perestroika period, on the occasion of the Nineteenth Party Conference held in Moscow in June 1988, Koval filed a petition for his release and rehabilitation, claiming that he was punished for his political opinions. However, this petition was rejected by the General Prosecutor of the MSSR in October 1988 on the grounds that Koval’s action was still “socially dangerous.” He was released in May 1990, when Article 203, part 1, of the Penal Code of the MSSR, on which Koval’s conviction was based, was abolished. He was definitively rehabilitated only in November 1991, following a special decision of the Supreme Court of the Republic of Moldova, which recognised that Koval’s case was political in nature (without explicitly condemning the use of punitive psychiatry). Koval’s fate after his release remains unknown.