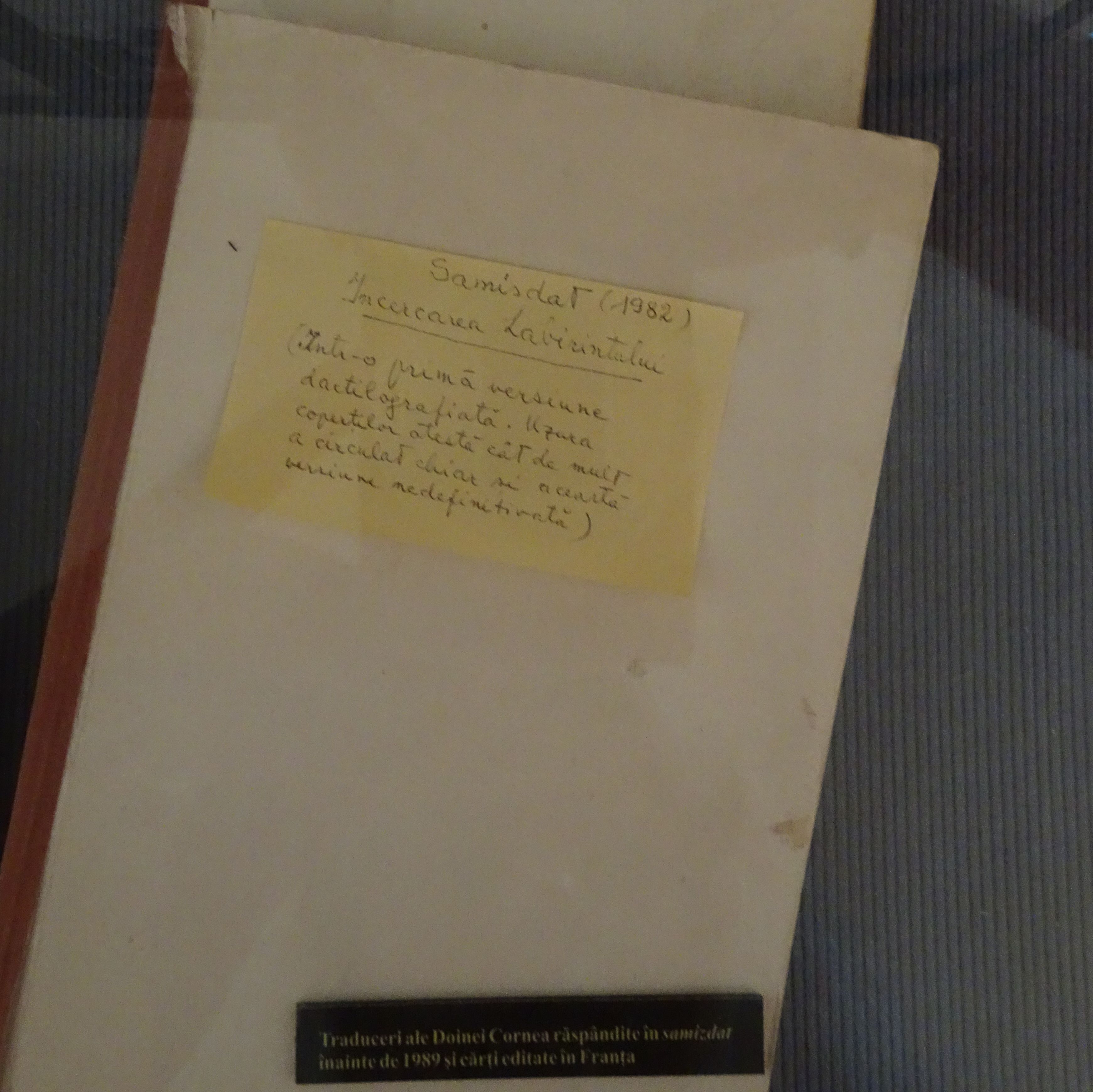

Mircea Eliades’s L'Épreuve du labyrinth: Entretiens avec Claude-Henri Rocquet (Ordeal by labyrinth: Conversations with Claude-Henri Rocquet) is the first book which Doina Cornea translated in 1982 in order to circulate it in communist Romania as a samizdat issue. The book found its way to Romania with the help of Doina Cornea’s daughter, Ariadna Combes, who had earlier taken advantage of a trip to France to emigrate. Using informal channels, she managed to send her mother many books that were not available in Romania. Among them, there was Mircea Eliades’s L'Épreuve du labyrinth, which had been published in 1978 (C. Petrescu 2013, 308–309). A former member of a group of very gifted young intellectuals (the so-called generation of 1927), Mircea Eliade was a prolific writer whose political affinities had been with the Iron Guard, the extreme right political movement in interwar Romania. Due to his encyclopaedic erudition, which proved instrumental after his emigration, Eliade later became a renowned historian of religions in the United States and informally the most famous member of the Romanian diaspora. Although the communist regime tried to recuperate Eliade in order to use him as agent of influence in the West, he was still a taboo person as a refugee and former supporter of the Iron Guard.

As a lecturer in French language and literature at the University of Cluj-Napoca, Doina Cornea translated L'Épreuve du labyrinth into Romanian and used it in her classes without any official approval. As she mentioned in the forward of the post-communist edition of her samizdat translation of Eliade’s book, her motivation for selecting it as a teaching material was to offer a role model to her students: “The young reader, who is unfortunately used to certain patterns of thinking, will be amazed from the beginning by the freedom, the openness and the creativity in Eliade’s thinking” (Eliade 1990, 5). This initiative and the letter sent to Radio Free Europe (RFE) in which she criticized the state of education in Romania led to her ousting from the university in the autumn of 1982. Forced into early retirement, Doina Cornea had thus more spare time to use for her dissident activities (C. Petrescu 2013, 308–309).

One of her first dissident actions was to further refine the Romanian translation of Eliades’s L'Épreuve du labyrinth and add explanatory notes for a wider readership (Cornea 2006, 73), in order to transform this manuscript into a widely distributed samizdat publication. The process was time consuming and also entailed high personal risks for Doina Cornea. As she remembers, she started to type the translation on very thin pages in order to make up to six copies at once using carbon paper (Cornea 1990). At that time the possession of a typewriter was strictly controlled by the communist regime. Anyone who wanted to have one was legally compelled to obtain an authorisation from the Militia. If permission was granted, the owner had to provide the same Militia with a typeface sample of the machine so that its unique characteristics could be registered. Additionally, a sample of its typing was to be provided at the beginning of every year, and also every time the typewriter was repaired (C. Petrescu 2013, 296-297). This measure allowed the authorities to quickly identify and punish the authors of samizdat publications or other types of presumably hostile writings such as leaflets and letters sent to the Romanian authorities or foreign radio stations. It also served to discourage those people who might nurture the idea of producing and distributing these texts by drastically decreasing their chance of not being identified by the Romanian secret police, the Securitate.

Apart from the high personal risk resulting from her being quickly identifiable from the typeface sample of her typewrite, Doina Cornea’s decision to multiply the translation of Eliade’s book also entailed high financial costs. At that time all photocopying machines were state owned and their use was strictly monitored by the communist authorities, especially by the Securitate. Thus, in addition to the significant cost of multiplying the many pages of the translation, Cornea or those who helped her probably had to buy the goodwill of the operator(s) of the photocopier so that they would turn a blind eye to what was being copied. Because other intellectuals refused to help her, Doina Cornea had to rely on the support of her son and his friends and also on the aid of her former students. All of them gladly made a small monthly contribution to help her pay for the photocopying of the manuscript and they also got involved in the dissemination of its 100 copies (Cornea 1999, 14).

The content of this samizdat, Mircea Eliades’s L'Épreuve du labyrinth, is in fact a book-length interview in which the Romanian historian of religions speaks about his early life and his many formative experiences. He talks about his extensive and diverse reading, about his scholarly interests in Oriental studies and especially in the history of religions and mythologies, and about his dissertation in philosophy. A lengthy discussion is given to the meaning of his trip to India, where he learned more about Indian cultures and religions. Following the experience of this spiritual voyage, he wrote some of his well-known literary pieces, such as Maitreyi (published in English translation as Bengal Nights), Nights in Serampore, and Isabel and the Waters of the Devil. Also in India, Eliade admitted that he became interested in politics, and in means (violent and non-violent) of fighting politically against discrimination. Although Mircea Eliade speaks about his time in Romania before his emigration to the West in 1940, he deliberately avoids any mention of his involvement in the activity of the extreme right political party, the Iron Guard. The rest of the book is concerned with his period of exile in Paris and Chicago, and traces step by step his method of research in the history of religions. It aimed not only at rediscovering the archaic roots of the spirituality and the blending of the sacred and the profane in the everyday life, but also at underlining the symbiotic relation between spirituality, freedom, and culture. Consequently, in the context of the book, the labyrinth becomes synonymous for Eliade’s initiatory journey into the realm of spirituality that helped him rediscover the new real, reality, and thus opened a door towards personal freedom, fulfilment and self-knowledge. Related to this, Mircea Eliade underlines the role that intellectuals have or should have in the formation and preservation of national spirituality and explains why their role as guardians of spirituality is even more important under dictatorial regimes such as communist ones (Cornea 1990, 5–6).

Apart from the rationale of providing Romanian readers, especially young readers, with an incentive to work on themselves following Eliade’s example, Doina Cornea’s motives for translating his book-length interview into Romanian also reflect their similar opinions. Like Mircea Eliade, Doina Cornea believed that spirituality (and the rediscovery of religion) was the only way to gain personal freedom. As she pointed out in many of her letters sent to RFE or in the interviews she gave, Cornea considered culture and religion as the best weapons with which to fight against communism and to secure freedom from the constraints and misery of daily life in a non-democratic regime (Cornea 2006; Jurju 2017). The translation and dissemination of the book L'Épreuve du labyrinth as a samizdat reflected Doina Cornea’s decision to serve as a guardian of authentic spirituality for young intellectuals living under a communist regime, thus fulfilling the important role that Mircea Eliade defined in his dialogue with the French writer Claude-Henri Rocquet.