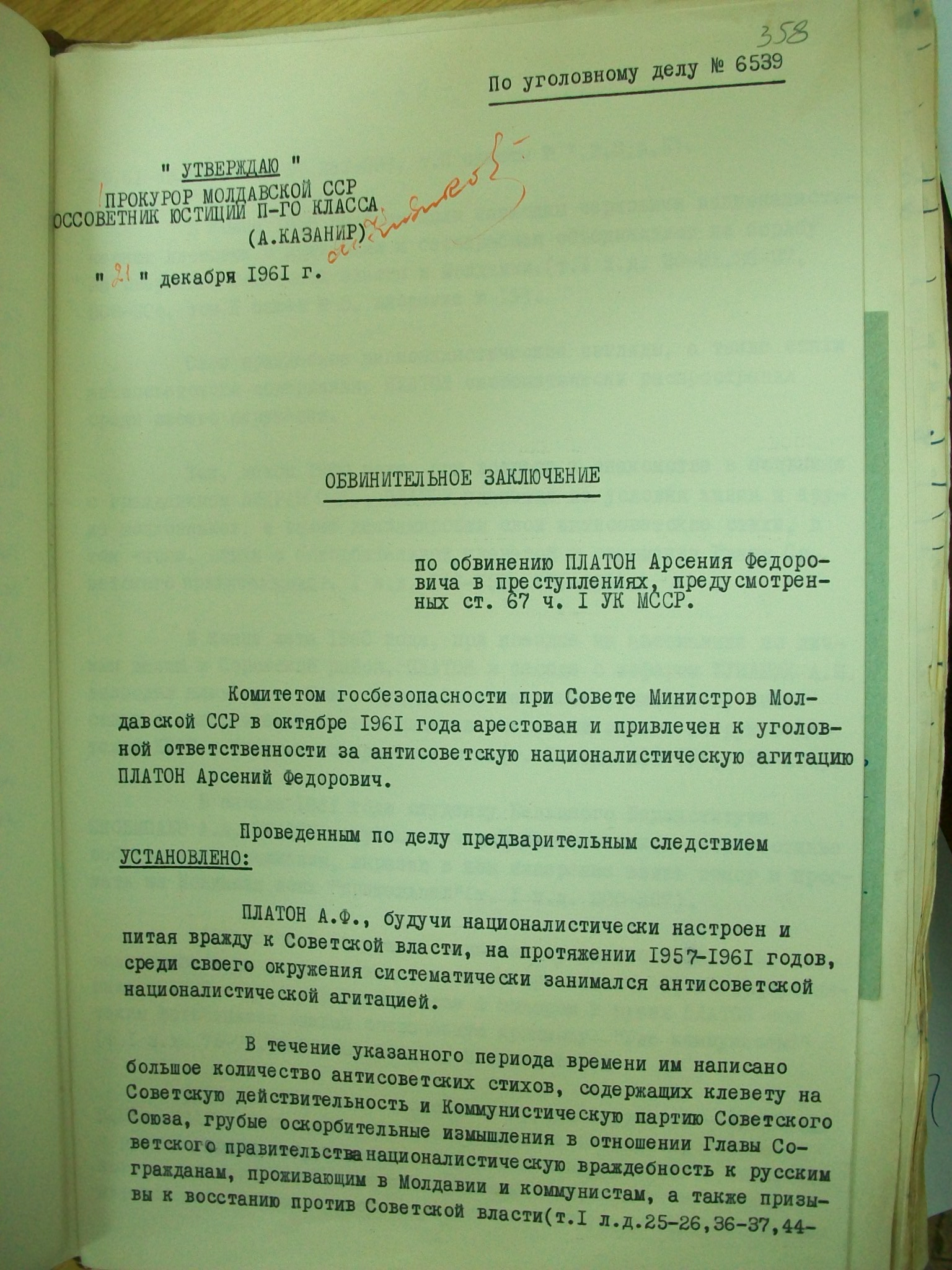

The official accusatory act concerning the case of Arsenie Platon (case No. 6539) was issued by the KGB investigator Captain Sidelnikov on 19 December 1961, when it was approved by the head of the Moldavian KGB, Major General Savchenko. This document was also approved by the Prosecutor General of the Moldavian SSR, A. Kazanir, on 21 December 1961. The accusatory act provided a concise and synthetic narrative of the main “anti-Soviet activities” conducted by the defendant during 1957–1961 and a detailed account of the accusations brought against Platon. The main count of indictment referred to the “anti-Soviet nationalist agitation” that Platon purportedly spread among his network of friends and acquaintances. Concretely, the defendant was accused of the following misdemeanours: “displaying a nationalist orientation and open hostility toward Soviet power, during 1957–61 he systematically conducted anti-Soviet agitation; he wrote and spread poems containing calumnies regarding Soviet reality and the CPSU, rude and insulting attacks against the Head of the Soviet government, as well as anti-Soviet nationalist fabrications, directed against communists and citizens of Russian origin residing in Moldavia; produced drafts of nationalist proclamations with open calls to the Bessarabians to unite in their fight for overthrowing Soviet power in Moldavia; spread among his milieu provocative nationalist fabrications and lies, expressing his discontent with Soviet power and with the presence of Russian people in Moldavia; propagated calumnies against Soviet reality, praising the living conditions during the former Romanian bourgeois regime; publicly read his anti-Soviet poems, which distorted and discredited the Soviet social system and the leaders of the Soviet state.” This fragment is revealing not only for the substance of Platon’s crimes in the eyes of the Soviet authorities, but also for the language and rhetoric used by the regime to categorise and classify various dissident and oppositional actions. It is clear that Platon’s nationalist views, the articulation of his opinions in public, as well as his draft proclamations and the favourable comparison of the Romanian regime to its Soviet counterpart were the most serious aspects of his case, which aggravated his situation further. Platon’s defence strategy, based on his denial of any public impact of his views and the obstinate refusal to confirm the witness accounts that incriminated him, ultimately backfired when the investigators adduced additional evidence and confronted him directly with the witnesses. It seems that his arrest was preceded by a denunciation made by several of his co-workers or fellow patients during his earlier time in the hospital, in the summer of 1961. Although this does not result clearly from his file, it is probable that the KGB had some hints of his suspicious behaviour, which explained the search of his house on 18 October 1961. The accusatory act also carefully traced Platon’s contacts during 1957–1961, emphasising the possible motivations and influences that might clarify his conversion to nationalism and his criticism of the regime. Despite Platon’s acceptance of the substance of the accusation and of his guilt, the accusatory act noted that the defendant’s “anti-Soviet views” were already apparent during his earlier prison term, in 1957, and thus contradicted Platon’s assertion that he only became disenchanted with the regime after 1959, under the influence of his co-worker, Nikolai Emelianov. The textual nature of Platon’s criticism and the possibility of a wider public impact of his views were especially worrying for the authorities. Despite the isolated and spontaneous character of his actions and the failure to prove Platon’s connection to any organised form of opposition, the radicalism of his nationalist rhetoric was enough to convince his KGB investigators of his potential danger. He was indicted according to article 67, part 1, of the Criminal Code of the Moldavian SSR (“anti-Soviet agitation and propaganda aimed at undermining Soviet power”) and sentenced to three and a half years of prison in a high-security labour correction colony. Following the usual pattern of the Soviet justice system, the sentence repeated almost literally the text of the accusatory act.