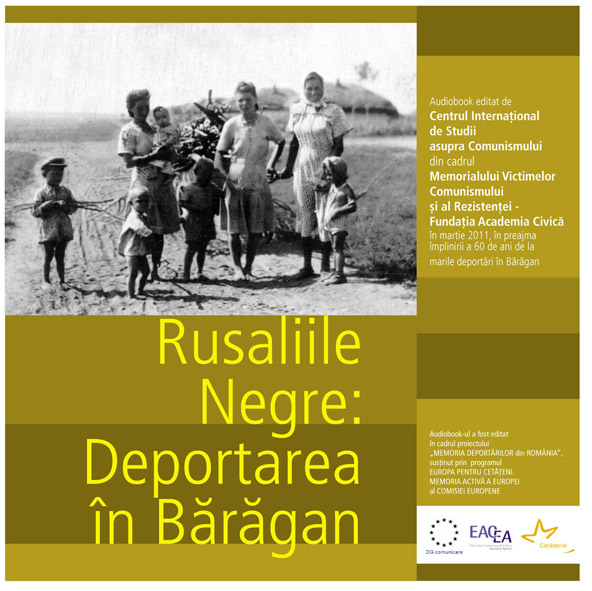

On the basis of the materials to be found in the oral history archive of the Sighet Memorial, a second audiobook was launched in 2011 under the title Rusaliile Negre: Deportarea în Bărăgan (Black Whitsunday: Deportation to the Bărăgan). The occasion for the launch of the audiobook was the sixtieth anniversary of the massive deportations from the west of Romania, from the border with Yugoslavia, to the Bărăgan, a vast plain in the south of the country, which at that time was almost completely uninhabited, a veritable Siberia in its isolation from the rest of the country and its minimal population density. The title alludes to the fact that this event took place on 17–18 June 1951, on the very day of the feast of Pentecost (Whitsunday), the seventh Sunday after Easter calculated according to the method used by the Orthodox Church. This multimedia document includes twenty extracts from seventeen interviews in the oral history archive of the International Centre for Studies into Communism, part of the Memorial to the Victims of Communism and to the Resistance. The editing was the work of Andreea Cârstea and the musical illustration is by Grigore Leşe. The audiobook was created as part of the project “Memory of the Romanian Deportations,” financed through the European Commission’s programme “Europe for Citizens: European Remembrance.”

Romulus Rusan, who coordinated this project, describes thus the drama experienced by those deported without guilt, without any prior notice, without the possibility of escaping the consequences of this arbitrary action, which targeted all those of whom it was suspected that they might have sympathised with the policies of the communist leader in neighbouring Yugoslavia, Iosip Broz Tito, who was already in open conflict with the leader of the Soviet Union, Iosif Vissarionovich Stalin: “The deportations from the Banat and Mehedinţi in the summer of 1951 were one (the most bestial) of the numerous projects of social purging invented by the communist regime in the Gheorghiu-Dej period, at the height of Soviet domination. Following a plan prepared over three months with diabolical precision, during the night of 17–18 July over 44,000 people were removed from their homes without any prior notice, starting with women and men fit for work and continuing with their families, comprising elderly people up to eighty-five years of age and children of all ages (one of them born just two days before). After a long-drawn-out journey of two weeks, locked in livestock wagons, the deportees were unloaded in a number of railway stations in the Bărăgan, from where trucks carried them to eighteen different points in the deserted steppe. Left to their own devices in the open, under the burning summer sun, they first had to make underground huts, as in a primitive village. In the years that followed they built themselves more presentable houses and brought the virgin soil under cultivation. They thus managed to obtain food for themselves and for their farm animals, overcoming poverty and isolation, surviving like so many Robinson Crusoes of the twentieth century.” The grandparents of one of the authors of the present text were among those hurriedly deported on that dark Whitsunday night, from a village near Timişoara, where they had settled after fleeing from Bessarabia. Leaving behind their house and their belongings for the second time, they were forcible moved to the middle of the Bărăgan, where they arrived with what they had been able to pack quickly and carry with them, where they were given nothing but a door and two windows, so they could make themselves a house of mud and reeds before the coming of winter, where they were forced to reorganise their entire existence in the middle of a deserted plain with almost no sources of water. Their children escaped deportation only because at that moment they were at university in Bucharest. So as not to share the fate of their parents, they falsified their birth certificates, changing their name and Bessarabian place of origin, which had been one of the reasons for the inclusion of their parents in the list of deportees. Romanians from Bessarabia who had taken refuge in Romania at the end of the war to escape the Soviet regime and were implicitly considered by the communist regime in Romania to be anti-Stalinists and potential Titoists, constituted the second largest group among the categories deported to the Bărăgan in June 1951.