The collection illustrates Adrian Marino’s intellectual evolution as a historian and literary critic who chose to pursue his activity outside the institutions controlled by the communist regime, and also the Romanian literary life of the period 1964–1989, and the way Romanian intellectuals related to the communist regime. After his release from house arrest in 1963, Marino started an intense cultural activity, trying to make up for the time lost in his fourteen years of detention and house arrest. He benefited from the relative cultural freedom at the end of the 1960s and the beginning of the 1970s. While documenting and drafting his studies of literary history and comparative literature, Marino purchased many books, depending on his academic interests at that moment, many of them from abroad. Thus, in the period 1964–1989, he succeeded, through his contacts and exchanges with Romanian and Western intellectuals, in gathering an impressive library, with numerous books in foreign languages, which were not accessible in the libraries of communist Romania. It included, among others, the books published by Mircea Eliade abroad, as Adrian Marino was preoccupied by the work of this Romanian writer and historian of religions who had defected to Western Europe in 1945. These books circulated among Marino’s collaborators and friends. As shown by the complaints he wrote to the communist authorities, who confiscated many books at customs, procuring and preserving such works was very difficult, especially in the 1980s, when the regime tightened its control over the circulation of cultural goods. Before 1989, the books that Marino bought covered especially his areas of expertise: literary history and criticism, comparative literature, Romanian and foreign literature. After 1989, the author profited from the fall of communism and freely expressed his interest in ideological books. Thus, after 1989, Marino purchased many books dealing with classical European liberalism, as well as books about history and politics.

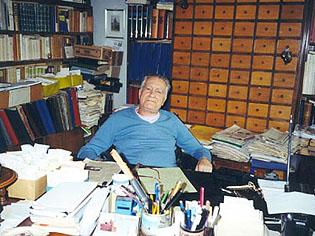

From the beginning of the 1960s, Adrian Marino collected and archived his correspondence with Romanian and foreign intellectuals, such as Matei Călinescu, Constantin Noica and Emil Cioran. This correspondence, in the context of the strict control of correspondence during the communist regime, illustrates, on the one hand, Adrian Marino’s ability to maintain close contacts and collaborations with Romanian and Western intellectuals, overcoming the difficulties raised by the communist authorities concerning the circulation of cultural goods and information. On the other hand, the correspondence contains many letters in which Marino critically analyses Romanian literary life and its relationship with the communist authorities. A distinctive feature of Adrian Marino was his constant preoccupation with preserving and organising his personal archive. With this in view, after 1989 he made copies of some letters he had sent in the communist period. The files containing his correspondence with certain personalities (such as the literary historian Matei Călinescu) thus include both the original letters received by Marino, and copies of the letters he sent. According to Florina Ilis, this preoccupation with a systematic correspondence, with its preservation, along with the entire personal archive can be explained by Marino’s interwar education. This archive, especially the correspondence, represented the basis for creating one of the masterpieces of the collection, namely Marino’s memoirs, entitled Viaţa unui om singur (The life of a lonely man). The author also saved the manuscripts and drafts of his work, which reflect the cultural activity of one of the few Romanian intellectuals who enjoyed international visibility despite living in Romania. Among these manuscripts, the memoirs represent one of the most well-structured and virulent attacks against the intellectuals of communist and post-communist Romania.

After 1989, Adrian Marino contemplated the possibility of donating his private collection to a public library. Doru Radosav, the former head of the Lucian Blaga Central University Library of Cluj-Napoca (BCU Cluj-Napoca), persuaded Adrian Marino to make this donation to the institution he was running. Thus, the donation deed was signed in March 1994, and in the period 1994–2005 around 600 files from the private archive were transferred: files containing manuscripts, drafts, correspondence, personal papers, clippings from Western and domestic press, photographs. Their archiving and inventorying, carried out by Florina Ilis together with Adrian Marino himself, combined Marino’s expressed wishes with the general principles of library science. After the author’s death in March 2005, his personal library was also transferred. Since 2006, BCU Cluj-Napoca has organised each year in March thematic commemorative exhibitions highlighting pieces from the collection, such as manuscripts, photographs, correspondence, or personal documents.