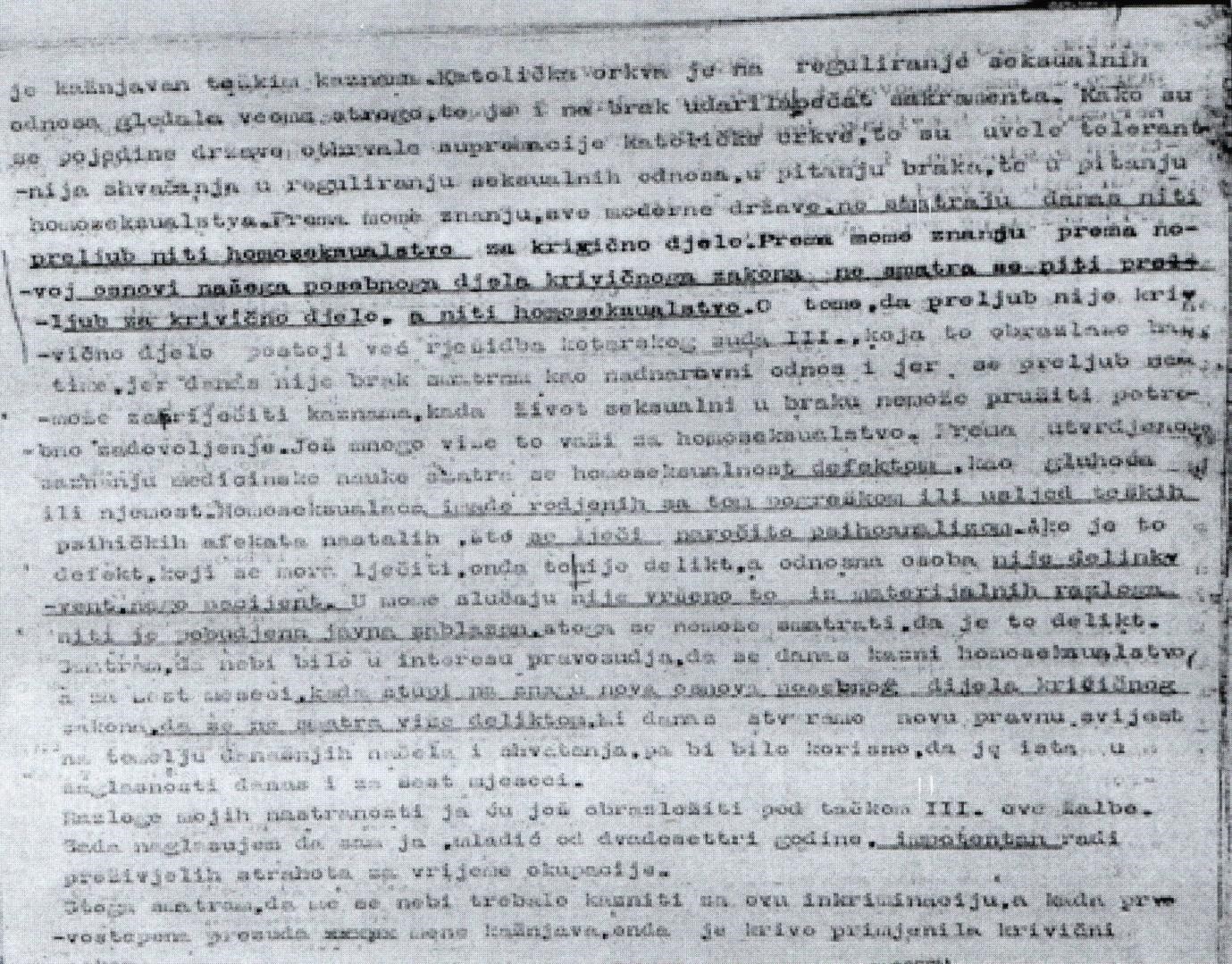

“I have been sentenced to 6 months in prison for unnatural fornication. I do not believe my behaviour should be punishable by law since it does not constitute a crime. From the most ancient times of human history, among the oldest civilizations, the Egyptians, Greeks, Persians, in the Islamic world, in Japan and China, this ‘unnatural fornication’ had been tolerated. It was only with the emergence of the Catholic Church and its supremacy that this fornication was proclaimed the sin of Sodom, and harshly punished […] Countries that managed to wrest themselves free from Catholic supremacy introduced more tolerant regulation of sexual matters, regarding marriage and even homosexuality. As far as I know, there is not a single modern state that would consider adultery or homosexuality crimes” (HR-DAZG-1007-527: “Žalba [Branka Vujaklije] na presudu Okružnog suda u Zagrebu K 236/949-7”, prosinca 1949. [Appeal (of Branko Vujaklija) against Zagreb District Court verdict K 236/949-7, December, 1949]).

With these words Branko Vujaklija, a 23-year-old theology student and Serbian Orthodox cleric from Zagreb, attempted to convince the Croatian Supreme Court to release him from prison where he was held for “unnatural fornication.”

During his trial, Vujaklija unapologetically declared he was homosexual. He tried to explain to the judge that he was only acting in accord with his “natural sexual instincts,” that his sexual relations were always with consenting adults and never in public, so therefore, Vujaklija argued, he could not have been declared guilty. The judge ignored his arguments, and found his acts extremely immoral (Dota 2017, 94-95). Vujaklija did not give up and wrote an appeal (part of which was quoted earlier). He changed his argument: since he was sentenced as a moral degenerate and a debauched bourgeois, this time Vujaklija himself decided to use ideological arguments as well. He tried to explain to the judges that the contempt towards homosexuality had its origins in the Catholic tradition that should have no place in a new, modern and progressive socialist society. However, his efforts were in vain, and the Supreme Court of Croatia rejected his appeal (Dota 2017, 95).

Both the court sentence and Vujaklija’s appeal were retrieved during Domino’s research, and thus became part of the Collection History of Homosexuality in Croatia. The 1949 verdict, as well as other related documents, including the cited appeal letter, were originally held in the State Archives in Zagreb (DAZG), and are part of the Zagreb County Court Fund (HR-DAZG-1007).

These documents testify to the ideological motivations behind the persecution of homosexuality in the post-revolutionary phase of communist Yugoslavia, but also to the resistance mounted by some sentenced homosexuals against the authorities. Vujaklija was bold and daring enough not only to depict his homosexuality as a completely natural phenomenon, but also to demand his own acquittal and the decriminalization of the same-sex sexual relations in general.